On April 6th 2024, me and a couple of friends (Tom and Ionie) moved from Birmingham to the Lake District, in an effort to put the mountains directly on our doorsteps. The plan was to boulder, climb, hike, scramble and any other outdoor activity we could think of, all while working our IT jobs remotely. Personally, my major ambition for this trip was to lead a significant volume of routes graded “HVS” – a grade that I have lead a couple of times before, but which provides ample challenge for me in terms of both the difficulty of the climbing and the ease of finding protection.

Unfortunately this was not to be, since on Sunday 14th April – after just one week of annual leave, I took a 10m ground fall from a route graded E1 (a harder grade than HVS) and suffered compound fractures in both of my ankles, effectively ending my outdoor season. Mercifully however, my head and spinal cord are both untouched, so whilst the road to recovery is currently uncertain; I am alive, unparalysed, and able to start work on the comeback, in whatever form it that ultimately takes.

As an exercise intended mostly to gain closure, but also because I will undoubtedly have to answer the question of “what happened” many times over the coming months, I figured it was better to go over the mistakes and nature of the accident in detail in a single place, rather than offering many different partial explanations to whoever might be interested. As such, this report is intended largely for a non-climbing audience, so it is worth opening with some brief explanations of British Trad Climbing.

British Trad Grades

A trad (or “traditionally protected”) climbing route is a route without bolts – meaning that as you ascend, you are searching for places to fit various bits of gear that you can clip the rope into in order to protect any potential falls. For this route, the only gear was “nuts” and “cams”.

In Britain, trad routes are given an ‘adjectival’ grade which attempts to capture the overall severity of the route, usually understood as a combination of the route’s technical difficulty as well as the ease of finding protection. Protecting trad moves is not always a guarantee, since you are relying on features of the rock to hold your gear in place, but as long as the moves are easy enough then a lack of protection does not always mean a massively high severity. Non-climbers might balk at the idea of positions that are essentially unprotected – positions where you’re only ever “one slip” away from disaster, but you need only consider a flat staircase or walking up a hill to understand that parts of a climb can be easy enough that they are not considered very severe, even when unprotected; provided you are a climber of appropriate standard.

The adjectival grade (the HVS, E1 grades mentioned earlier) gives you good ballpark figure to aim at, but more context clues are always needed before making a final decision to lead: route descriptions, online comments, the look of the route from the ground are all invaluable resources that can critically influence your decision.

So while it is true that E1 was in principle too steep a grade for me – a grade that cut out way too much of my margin for error – and that I should have stuck with my original plan to only lead HVSes this trip, the decision was not made completely indiscriminately. In fact, on our previous day of trad climbing, we had considered a HVS, but determined that the available protection looked too poor and we backed out. Instead, we decided to set up a (completely safe) “top rope” on an E2 route which, incidentally, all three of us managed to climb cleanly (i.e. without rests or falls) – although admittedly some the moves we made would have felt very desperate on lead.

The point I am making here is that while grades are certainly a relevant factor, they are not the be all and end all, and the precise mistakes I made in selecting this particular route are perhaps more instructive than the general over-ambition I displayed by selecting a route of this grade in the first place.

One other thing to mention about these grades before moving on is that they are a system used exclusively in Britain, and so in accordance with our national way, we have made them pointlessly arcane. In escalating order of difficulty, the grades are ordered:

- Difficult (D)

- Hard Difficult (HDiff)

- Very Difficult (VDiff)

- Severe (S)

- Hard Severe (HS)

- Very Severe (VS)

- Hard Very Severe (HVS)

- Extreme 1 (E1)

- E2, E3, etc..

In what follows I will refer to these grades freely, so it might be worth referring back.

The build up

After being rained off multiple times over the previous week and seeing the forecast for the day predict rain at either 3 or 5 in the afternoon, we decided to go to a fairly small, local crag that we had scouted out but not climbed at earlier in the week. As the routes here were all listed at under 18m tall, we decided to save space in our bags and only take our newly acquired 40m rope rather than the 70m one we had been using previously.

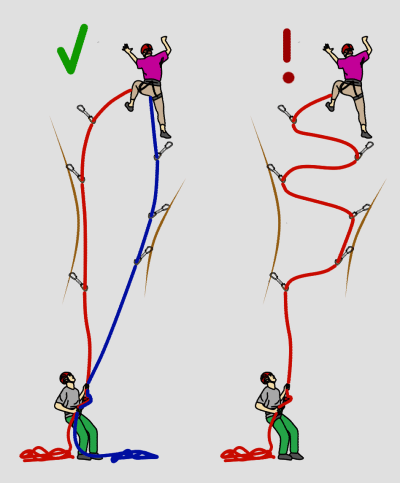

This length should still allow the lead climber to tie into the middle of the rope, using either side to clip into protection, which prevents the rope snaking from left to right and pulling on gear awkwardly as the climber ascends (see fig 1). the next two climbers who follow the route up can just climb up one strand each, making this a very efficient set up for climbing in a three – perfect for us.

I started the day by leading “The Slab”, a VS route which looked to have a bold but easy start, followed by a short section of well protected difficulty at the top. As it happens, I found quite good gear placements all along the route and ultimately found the climb to be a very pleasant warm up.

We did have one issue on it though: the boulder that I wanted to use for my anchor at the top was too far back from the top of the cliff, so the rope couldn’t reach it. After faffing about searching for alternatives, we decided that I should unclip from the middle and tie in to one end, so that I could use the full length of the rope to just anchor around the boulder that I originally wanted to.

I only mention this because this issue cascaded onto Tom’s next climb, who lead “Cub Crack” (Grade:HS). He reasoned that his climb was in a straight enough line that it would be preferable to climb on only one end of the rope, meaning he didn’t have to worry about the prospect of running out of rope at the top. This was a fine decision for the climb, which also went well for all three of us.

At this point, we were thoroughly warmed up and had already done what looked like the two most attractive ‘easy routes’ on the crag, so it would perhaps have been the ideal time to move onto a HVS, if only there were any around!

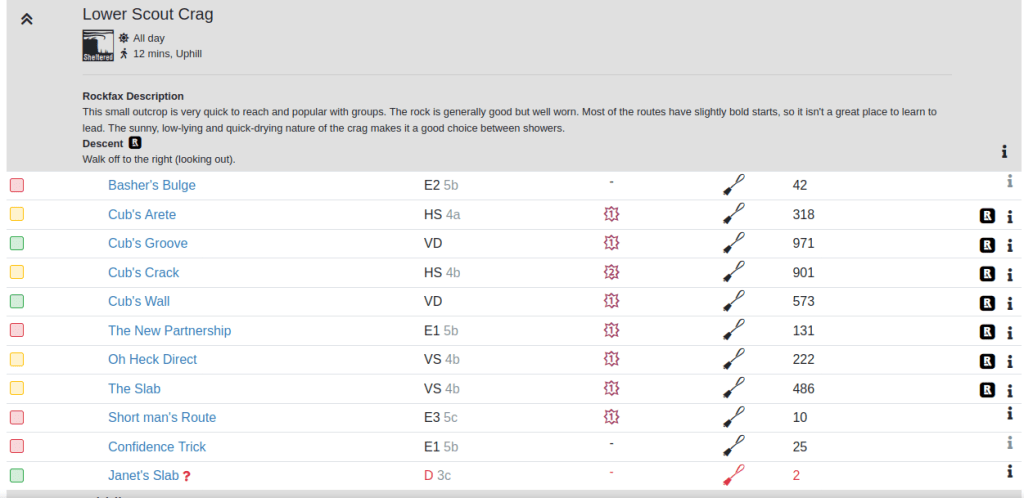

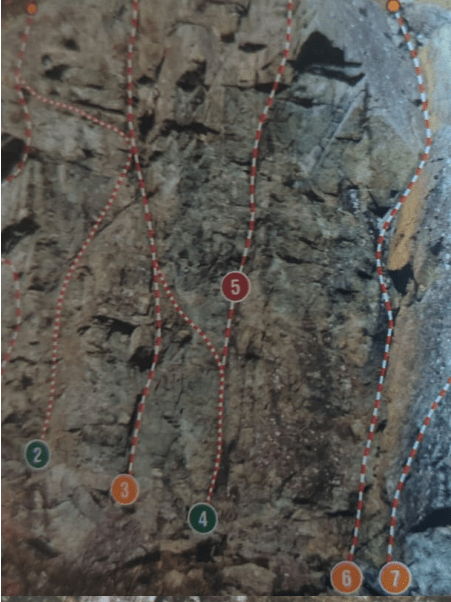

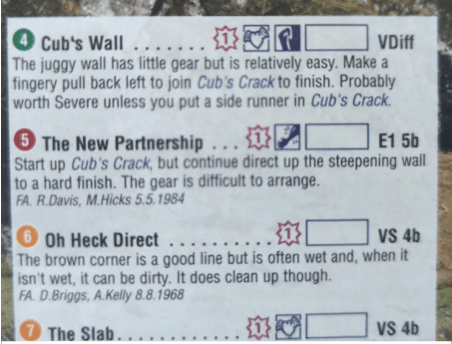

The final VS route (Oh Heck Direct) was described by the guidebook (and confirmed by our eyes) to often be wet and dirty – which is not a very attractive proposition. It seemed pointless to move crags (when the directly neighbouring crags wouldn’t really have accommodated our 40m rope anyway), or to move onto easier routes than the ones we had already warmed up on, so our attention naturally turned towards the E grade routes. We could very well have set up a top rope on one of these, just as we had done two days prior, but I had to admit that the line for “ The New Partnership” (route 5 in the rockfax guide) looked quite compelling to me:

Interestingly, the main guidebook we were using this day – the one simply titled “langdale” – had a significantly different route and line described here, and while that description didn’t mention the difficult gear, I don’t think this was necessarily very consequential.

To explain what I was seeing on the ground: this route started with very easy, although difficult to protect, terrain up to about 4/5 metres high, just after the route split off from the much easier ‘cub’s wall’. The fact that this section would be easy climbing was confirmed by the fact that cub’s wall itself was a Vdiff (albeit a VDiff with a ‘fluttery heart’ symbol, indicating particularly unprotected climbing). At about the 5 meter mark on my route though, there was a large flake of rock that I could more or less see from the ground would hold a good cam. After that, the climbing again looked like quite an easy (but still poorly protected) line up to a good, if narrow, standing ledge at about 8 and a half metres high. When standing on that ledge, at around chest height, there appeared to be a good crack feature that would hold some form of gear, even though I couldn’t tell quite what it would take from the ground. This ledge stood directly below a large overhanging “nose” feature, with some quite obvious hand holds on it that you were supposed to climb directly through. The nose was undoubtedly the difficulty that justified the climb’s E1 grade.

Leading this route was quite attractive to me, because I figured that a lot of the route would be done with minimal gear placements, but then at the points where I really needed to put in something good – on the first flake, and just before the big moves over the nose – then I would have as long as I needed to stand on the ledge and place the right pieces before committing. That style of placement suits me well, because it means I don’t have to manage placements from tiring hanging positions, which I often find I lack the stamina to do effectively.

It also looked like, if for whatever reason I needed to, I might be able to escape along the ledge to the left at the top, without needing to go over the nose directly, but I have to admit that this plan was something I had only idly considered, rather than genuinely mapped out. Tom seemed interested in leading the route too, and we did suggest that he try and lead it first since he is a better climber than me with significantly more trad experience. I do not know if he would have attempted to lead it on sight as I did, or sensibly suggest we setup a top rope first, but as it was my ‘turn’ to lead a route anyway, I got the first decision, and I decided I wanted to go for it.

Once the decision had been made to climb, we automatically began uncoiling the rope, with almost no discussion, in a way that assumed I would be going up on one end rather than the middle. In hindsight, this was a poor decision which made the prospect of escaping left onto the top ledge more difficult, because all my gear would now have to be placed more in line than if I had two separate strands to utilise. But since I hadn’t properly conceived of – or communicated – the idea of escaping onto the ledge at all, and all the gear along my actual route did seem to be reasonably in line, I figured the choice didn’t actually matter that much. Ultimately, I can’t know whether this could have made a critical difference or not. What I do know though is that once I got onto the ledge, I did see a potential gear placement quite far out left, but dismissed it, because placing it would have pulled the rope too far away from my other placements.

These are the kind of compounding stupidities that will annoy you most after an accident; I was not climbing on one end of the rope because I thought it was the right decision for the route – I was climbing on one end because we wanted to try out our new rope, and so we brought one that was basically too short for the crag.

The Climb

The climb began more or less as I had expected, although I did manage to find a sneaky micronut placement before the first flake which actually looked pretty good to me, despite being inexperienced with micronuts and not particularly trusting them in the best of circumstances. Once I got hold of the flake, I could place the cam that I expected to, and I actually ended up putting one at the bottom (a purple) as soon as I arrived at the feature, and putting another cam ( a green) at the top of the feature, to ensure I had the highest placement possible before committing to the short unprotected section up to the ledge. Again, as expected, the next section of climbing was fairly easy and I felt secure the whole way up – although that didn’t stop me from faffing around for a while trying to place a dubious nut somewhere before I abandoned the idea.

The “ledge”, however, was not as I’d hoped. Firstly and most importantly, the “crack feature” whose shadow had looked so obvious from the ground, was revealed to be – as these features sometimes are – a flaring, multifaceted beast, without any of the obvious gear placements I had anticipated. Secondly, when I stood up on the ledge, the overhanging nose above was actually pushing my chest backwards away from the wall, so although the ledge did just about allow for a no hands rest, doing so felt precariously imbalanced. This feeling was particularly acute before I’d found any gear to place, and my initial moment on the ledge was spent contemplating just how far below me my previous piece of protection actually was.

Still, my position was stable and I could remain composed, eventually finding a slightly shallow, square slot at knee height that looked like it would take a cam. After carefully scooting my hands down to it, I tried the red cam only to find that this was too small: despite fitting perfectly in the depth of the slot, it was too narrow and had barely any camming action against the walls. I quickly swapped it out for the next size up (the yellow), only to find that although this one cammed against the walls quite well, it only fit quite shallowly into the slot. This concerned me – but I was somewhat reassured after the placement survived a couple of hard yanks.

Standing up to look for more back up, I tried endlessly to fit various nuts into various strange constrictions, but the only one that seemed at all successful was a particularly small micronut found at eye level. The constriction was once again quite shallow, but it’s angle was steep and it seemed to hold the shape of the offset nut very snugly. Feeling a little more secure with these pieces in, I tried to relax and look around. I looked out left to see the ledge continue across, with a potentially useful pocket at eye level. The traverse over to it definitely looked possible, although not trivial, and this is the piece I think I would have investigated more had I been climbing on two ropes. But since I wasn’t, I didn’t bother.

Having satisfied myself that there wasn’t any more obvious gear around, I allowed myself a lengthy rest on the ledge to regain stamina and composure, before leaning out upwards to grab some good, yet intimidating, holds on the nose. Willing to step up now onto a higher foot, I pulled away from the wall on a good hand hold and quickly felt around with my free hand for a couple of higher cracks that looked like they might have taken some gear. What I felt was once again disappointing, so I carefully stepped back down onto the ledge to regain composure a second time. Once I felt ready to climb again, I quickly made two quite powerful, but secure enough feeling moves further, with the aim of investigating a higher pocket that had also looked promising from the ledge. It looked like it should be able to hold the smallest grey cam, so I jammed one in – but didn’t like how it looked with only three of the four lobes applying pressure to the rock. The more I faffed around with it in the pumpy overhung position though, the more composure I lost, until eventually I just said screw it, I’ll treat this piece as bonus “nice to have” protection, and quickly clipped into it before retreating once more on to the ledge.

From Tom’s perspective here: I had spent a long time placing gear on the ledge which I described as “not ideal” – I then moved a bit higher and struggled placing another bit overhead, from a somewhat insecure looking stance, which I clipped as quickly as possible while announcing that I would have to step back down again. It is no surprise that once I got back down to the ledge, I could now feel some tension in the rope. The trouble with this was that the rope was now being pulled somewhat tightly through my highest piece of gear – the dodgy grey cam – which meant that the direction of pull on my lower pieces – in particular on the middling micronut – would now be upwards; the exact opposite of how I had intended that placement.

This final attempted rest is, to my mind, the critical juncture where I could have made better decisions. If I decided that I did ultimately trust my three placements, then I should have looked to extend the clips to some of them so that they were all working in harmony with each other, rather than in opposition – and I should also have had the confidence to ask for a slack belay, to minimise the shock that would be loaded onto the gear in the event of a fall.

If I decided that I did not trust these three pieces enough, then I should have taken yet more time to look for other viable placements. If I couldn’t find any, then I might seriously have had to consider a plan of retreat – either via an attempted down climb or out left onto the ledge as I had originally imagined. Retreating would still be a risky proposition – but it would at least mean abandoning thoughts of finishing the “intended route” and recognising that I was now in a survival situation; two things which I didn’t ever really do.

Instead, what I did here was to feel some false reassurance from the slight tension felt in the rope, decided that I should not waste any more ‘time’ or ‘strength’ looking for gear in uncomfortable positions and so I convinced myself that “one of my three pieces will surely hold” and besides, if I just did the next moves confidently enough, then it wouldn’t matter how good the placements were anyway. I suspect that if I had fully committed even to this poor plan, then I would have made it. But on my first proper attempt, as soon as I had both my hands and chest in line with the grey cam, with my feet on two good, but incutting, spots and I was looking up at a huge reach to the next probable hold, I lost my nerve. I tried to retreat back down to the ledge as I had done previously, but this time I moved my hand down to the wrong spot and ended up in an awkward, unfamiliar position. Unsure what exactly to do – whether I should even be trying to move up or down, and with one eye fixed on the horrible grey cam placement, I panicked and ‘decided’ to let go in such a way that might maximise the cam’s chance of staying in the wall.

As soon as I had done this, I watched in horror as it rolled it’s way out of the pocket. The only feeling I remember as I fell was anticipation that some piece must surely catch me. Unfortunately, the first piece to catch was the green cam, placed way back down on the flake, and this only served to offer some tension in the rope after I’d already fallen the full 10m and was hitting the ground. All three pieces I had placed above the ledge came out, and I am told they took some chunks of rock of with them. My best guess is that the Yellow cam, which was the best placement of the three, had broken rock off from the sides of it’s walls – whilst the nut had simply maneuvered it’s own way out, no doubt encouraged by the shoddy grey cam, but I couldn’t say this for certain.

Aftermath

Reading online comments about the route after the incident, I can see a general consensus from people (who are presumably all confident E1 climbers) that the gear options are all quite bad (https://www.ukclimbing.com/logbook/crags/scout_crags-340/the_new_partnership-7095). If I was inclined to drive myself mad, I could think about how I should have consulted these comments before attempting the climb – but I suspect that even if I did, I might have gravitated towards the comment the said “actually thought the gear was fine” to justify the desire I already had to do the route.

At the end of the day, climbing is for me primarily an adventure sport, and adventures are inherently dangerous. I am at peace with the fact that I was injured doing something that I knew would be bold, under a not unreasonable belief that I could do it safely, and that this belief simply got exposed as wrong. The more significant area of self reflection for me is just why I did these things so impatiently, rather than using more methodical progressions? why didn’t I top rope the route first, then redpoint it, and repeat that process until I felt comfortable enough to reliably try and onsight E1? Why didn’t I err further on the side of caution – as I told myself I would – on the first month of my holiday? As I’m sure the reader has their own navels to gaze at, I’ll leave the account here for now without delving deeper into these questions.

Acknowledgements

Nothing will make you realise how selfish it is to fall off a cliff than seeing the Langdale/Ambleside Mountain Rescue team, and the Northwest Air Ambulance – two organisations staffed entirely by volunteers – freely share their competence and time where it is needed most.

I’d also like to thank Tom and Ionie, who had Mountain Rescue on the phone immediately and brought me everything I needed on my first night in the hospital, without which I think I would now have gone completely insane.

Also all the friends, family and colleagues who have sent well wishes and more my way since the accident.

And last, but by no means least, I’d like to thank whoever invented those bottle that you can pee into sideways whilst lying mostly on your back.

Leave a comment